Harbinger of Hope: How Mothman Became a Lighthouse for the Othered

By Camille Maria Acosta

“You’re not a monster,’ I said.

But I lied.

What I really wanted to say was that a monster is not such a terrible thing to be.

From the Latin root monstrum, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: centaur, griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal,

a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.”

– Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

Display caption

Image: An artist rendering of Mothman by Tim Bertelink. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a cryptid is, “a creature that is found in stories and that some people believe exists or say they have seen, but that has never been proven to exist.” The Oxford English Dictionary states that a cryptid is, “an animal whose existence or survival is disputed or unsubstantiated.” Taking a look at these definitions, there lies a common thread – a being whose existence is constantly in question; a being whose worth is determined by societal measures; a being who often does not belong. Growing up a proud daughter of a Mexican immigrant, I was no stranger to the fantastical tales of legendary monsters. From El Chupacabra to La Llorona; monsters stitched together my existence from the day I was born. Cuddling up with my stuffed animals while my father screamed like El Cucuy is among my favorite memories of childhood – memories in which I never felt more seen. It wasn’t until I grew up that I realized for marginalized groups, telling these monstrous stories weaves a safer path forward for our existence; a path of survival when the world ostracizes you for who you are. Now living in Kentucky, I’ve learned that cryptids have continued to build those bridges where others build walls. And in Appalachia, a particular cryptid has built a community in which otherness is celebrated and in fact, has become a sanctuary for the different – Mothman.

As legend has it, on November 15th, 1966 four eyewitnesses originated the first ever sighting of Mothman in Point Pleasant, West Virginia. Linda Scarberry, Roger Scarberry, Mary Mallette, and Steve Mallette were chased in their car for miles by a seven-foot tall dark figure with glowing red eyes. After making the headlines in the Point Pleasant Registry the very next morning, the sightings only multiplied, often claiming that Mothman was seen before tragedy struck. One sighting stated that Mothman was visible during the Silver Bridge collapse in 1967 in which forty-six people perished. With sightings expanding across the country, such as one account taking place by the World Trade Center in 2001, Mothman quickly became synonymous with a warning, an omen. If Mothman was spotted, horror would soon follow. As the years progressed to the present day, Mothman has expanded from “Harbinger of Doom” to “Harbinger of Belonging”.

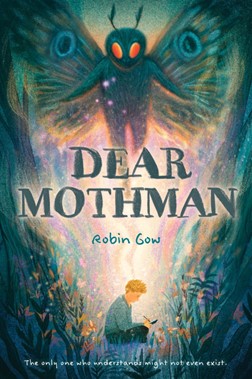

Today’s world is complicated. Hatred of those different from you seems to be a commonality across the United States. Queer bodies and Trans folks are being weaponized as “monstrous.” It is no question that marginalized Appalachians see themselves in Mothman, a being deemed horrifying by society; a being who never had the chance to tell their side of the story. The reclamation of Mothman as a gentle being powerful enough to defend himself has inspired ostracized groups across Appalachia to keep going. For many, identifying as a Queer Appalachian can feel terrifying, isolating, and painful. However, Appalachian folk literature has reshaped the traditional Mothman legend into one of Queer hope. For example, Pennsylvanian author and poet Robin Gow’s Dear Mothman explores transness, youth, and grief through the lens of the monstrous Mothman. One of the pivotal aspects of the book is the fear that queer children aren’t often listened to, validated, or believed, much like monsters. It is beautiful to see how Mothman has become a medium to explore the pain of otherization, and the beauty of embracing your differences.

Display caption

Image: Cover of Dear Mothman by Robin Gow: Credit: Robin Gow and Goodreads.

Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking with world traveling artist and metal worker Jami Honey about the importance of community. They mentioned, “community means being willing to publish a dictionary together…people with a shared language.” I like to picture a dictionary of Appalachian cryptids, filled with the personal experience narratives of those humans purposefully left out of history books. On every page, photos of brave souls redefining what it means to be monstrous; reclaiming the term as one of strength and courage. And under Mothman’s section, it reads,

“Mothman: A seven-foot tall moth-like being who loves to read horror books and take long flights

along the Ohio River. An entity who may come off as shy at first, but would be thrilled if you

took the time to get to know them. A cryptid whose legend was written without them knowing –

and one who is ready to take their story back. A Harbinger of Hope, to remind you that

you are never truly alone, no matter how ‘monstrous’ you may seem.”

Display caption

Image: Natalia Lucero shows Camille Maria Acosta their Mothman

plushie on Season 2 Episode 7 of the Floaties for Krakens podcast.

Credit: Camille Maria Acosta.

Camille Maria Acosta is a folklorist and monster enthusiast originally from the border town of El Paso, Texas. She pursued Performance Studies with a BA in Theatre from El Paso Community College and Western Kentucky University before completing her MA in Folk Studies from the same institution. Within this program, she delved into the beauty of Latinx horror through the lens of La Llorona, and how monsters are mirrors guiding us toward our own brilliance, our own truth. Upon graduating in 2021, she pursued folklore and cultural studies work with the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress as well as the New Mexico Arts Folk Arts Program, culminating in the YouTube documentary La Llorona: Picante pero Sabroso. Her work has been featured in several publications including De Los: Los Angeles Times, HipLATINA, Borderlore, and the two-part Tubi documentary series Scariest Monsters in America and Scariest Monsters in the World. In 2023, Acosta launched her podcast Floaties for Krakens, diving into the world of the other and exploring how being monstrous is synonymous with a powerful resilience. Today, she is fulfilling the position of Folklife Specialist under the Kentucky Folklife Program.

Citations:

Chappell, B. (2025, October 1). Devotees of the Mysterious Mothman descend on its West Virginia Hometown. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/g-s1-90648/mothman-festival-point-pleasant-west-virginia

Gow, R. (2023). Dear Mothman. Abrams.

Mallow, G. (2021, June 7). An Ode to a Hometown Creature: Mothman of Point Pleasant, West Virginia. Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage Magazine. https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/mothman-point-pleasant-west-virginia

Vuong, O. (2019). On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Penguin Press.

Zarka, Dr. E. (2019, October 16). Mothman: America’s Notorious Winged Monster | Monstrum. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GUpeDwiD64M